'Inside The Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment', Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam

The origin of perhaps the most important, yet misunderstood idea in teaching.

There was a conversation on BlueSky this week about the decline of ‘spicy’ #educhat on social media.

Some blamed the promotion to SLT of previously controversial bloggers. Others argued that there were no ‘big things’ left to debate.

This last point reminded me of this 2018 quote from Dylan Wiliam, taken from an interview with Greg Ashman.

“We need to stop looking for the next ‘big thing’ and instead do the last big thing properly.”

Dylan Wiliam

Formative assessment was the ‘last big thing’ Wiliam was alluding to in this quote and despite the evidence for its effectiveness, it remains probably the most misunderstood, and misapplied idea in teaching & learning.

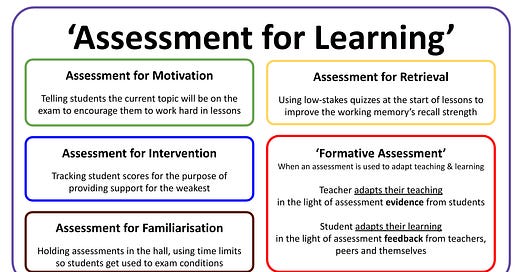

For instance, a common misapprehension is that ‘formative assessment’ and ‘assessment for learning’ are the same thing.

According to Wiliam, formative assessment is an example of assessment for learning, but not all assessment for learning is formative. For example, using low-stakes quizzes to improve retrieval strength is a form of AfL because it is an assessment that improves learning, but unless the teacher uses the results of the quizzes to change their teaching then it is not ‘formative’. It has not (in)formed subsequent teaching.

OK, I’ve used the F-word (formative) a few times now, so let’s take at look at its origins in ‘Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment’.

Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam were colleagues at Kings College, London when in 1998 they published ‘Inside the Black Box’. The paper coined the term ‘formative assessment’ and would shape teacher education for a generation and more.

The paper is a 9-page summary of a much larger research review conducted by Black and Wiliam into the use of assessment in the classroom.

It begins with its fundamental conclusion:

“We start from the self-evident proposition that teaching and learning must be interactive”.

At the heart of the paper are three questions:

Is there research evidence that formative assessment improves standards?

Is there research evidence that formative assessment is absent or improperly used in classrooms?

Is there research evidence about how to implement formative assessment?

According to the paper, the answer to the first question is YES. Black and Wiliam argue that their research review revealed an effect size of between 0.4 and 0.7 when formative assessment is used effectively. All things being equal this amounts to several months of progress above those that can be achieved without such a change in teacher practice. Significantly, the paper argues that the gains that can be made through formative assessment are particularly noticeable with students with lower levels of prior attainment. Suggesting that formative assessment can help students on the grade 4/5 boundary make life-changing improvements to their learning.

According to the paper, the answer to the second question is YES. The paper describes a ‘poverty of practice’ in the area of assessment. Problems include:

Assessments focus on the accumulation of facts over deeper understanding

Failing to share analysis of student understanding with other teachers

There is a tendency to place importance on the presentation of work

Giving marks and grades is over-emphasised. There is a lack of comments on how to improve.

The comparative performance of students is shared, which undermines the self-esteem and causes many learners to believe they lack ‘ability’.

Assessments that are designed to imitate external examinations rather than to test improvement in an area of weakness.

Time being devoted to holding so many assessments with the purpose of filling markbooks instead of analysing the results.

According to the paper, the answer to the third question is PARTLY YES. In the limited space available (its a 9-page summary) the paper focuses on the need for teachers to respond to assessment data - in particular by reteaching content that has not been learned. It warns on the use of excessively negative comments or comparative marking which might harm the self-esteem of the learner. It also places emphasis on the greater discussion of their learning by teachers and students e.g. by teachers addressing ‘common misconceptions’ with students. Interestingly, a need for greater ‘wait time’ during questioning is also mentioned. But, as outlined below, the detail on how to implement formative assessment is not found in ‘Inside the Black Box’.

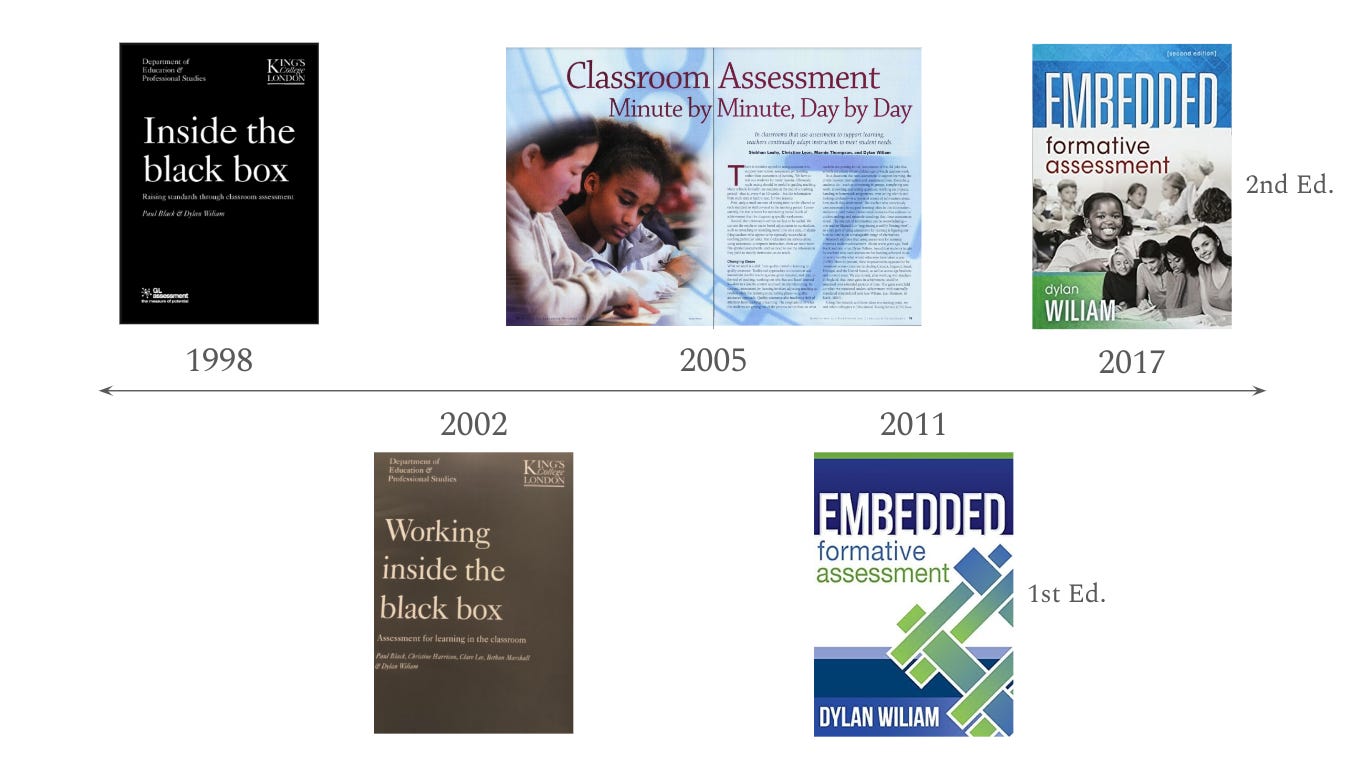

Wiliam continued to explore formative assessment in many subsequent publications. The most important of which were:

Working Inside the Black Box (2002), Black, Harrison, Marshall & Wiliam - This pamphlet is a report on a teacher training programme which aimed to improve the use of formative assessment.

Classroom Assessment: Minute by Minute, Day by Day (2005), Leahy & Wiliam - This chapter introduced five strategies for using formative assessment. These being:

Clarifying, sharing and understanding learning intentions

Engineering effective discussions, tasks and activities that elicit evidence of learning

Proving feedback that moves learners forward

Activate students as learning resources for one another

Activating students as owners of their own learning

Embedded Formative Assessment, 1st Edition (2011), Wiliam - This book offered in-depth practical advice on using the five formative assessment strategies in the classroom. A second edition was published in 2017.

Of the three, 2005’s ‘Classroom Assessment: Minute by Minute, Day by Day’ has been the most influential. Although not always in the ways Leahy & Wiliam intended.

A number of the chapter’s five strategies ended up suffering from ‘lethal mutations’ when implemented by teachers.

Perhaps most famously, the first strategy led to many schools requiring teachers to write ‘learning objectives’ on the board at the start of every lesson. This misunderstood Leahy & Wiliam’s intention that learning goals be shared at the higher curricular level, e.g. ‘we are studying this unit to learn why Hitler came to power’ not the granular lesson level. Additionally, lesson objectives were often too vague/abstract for students to understand without the subsequent context of the lesson, so each lesson began with students copying out sentences the meaning of which they did not comprehend (and wasting time to boot). Lastly, these objectives were confused with lists of (often differentiated) learning outcomes - all, most, some etc.

The second strategy led to massive increases in formal testing; resulting in every school implementing large programmes of data tracking and teacher intervention. This misunderstood the suggestion to use more informal testing multiple times each lesson to adapt teaching on the hoof. Instead many schools implemented half-termly assessments with massive tracking and intervention programmes following up the results.

The third strategy focused on feedback. When implemented poorly this strategy led to a heavy teacher workload in the form of great screeds of written comments. These were often written at the end of the half-termly assessment next the mark given. Consequently the student paid little attention to the ‘formative comments’ and instead obsessed about their mark.

The focus on learning objectives, data collection and written feedback has led to a lack of emphasis on peer and self-assessment (the fourth and fifth strategies). This has infantilised many students. Instead of being able to quality check their own work, they rely on teacher advice. Wiliam recently said that “good feedback works towards its own redundancy”. In other words we should be focusing our efforts on enabling students to accurately diagnose the weaknesses in their own work and make effective suggestions for improvement.

Some takeaways for teaching from ‘Inside the Black Box’ and Wiliam’s subsequent work on formative assessment include:

In the words of Wiliam, “teaching needs to shift from a linear process, to a contingent one”. We should only move on to a new topic once students have informed us us that they have understood the current one.

Research suggests that using more ‘formative assessment’ has a large impact on student learning.

Formative assessment should be used in every lesson; we shouldn’t wait for the half-termly or termly assessment to adapt or intervene. Ditch writing ‘lesson objectives’ at the start of the lesson and do some retrieval practice - but if you want it to be ‘formative’ use it to inform what is taught next.

Formative assessment is best achieved by using whole-class assessment e.g. whiteboards, ‘heads down, hands up’ or quizzing platforms etc. rather than individual questioning.

If we use regular in-lesson assessment, a form of ‘upstream’ intervention, there should be less need for major ‘downstream’ interventions after formal assessments like mocks. This can have a beneficial impact on workload.

Feedback should rely less on teachers providing extensive written comments on every script but instead model a quality response and then ask students to identify the differences between their work and the model answer. With the aid of appropriate prompts and suggestions, students should then be required to improve their work. We want teacher feedback to become ‘redundant’.

Lastly, teachers should use peer and self-assessment more often. This is a complicated area of practice - it can be easily done badly. So perhaps this is the ‘Next Big (Old) Thing’ that teachers should be discussing online.